- PzKpfw3 IV Ausf. D

- Sint Lenaarts, Belgium

- May 13th, 1940

- 2. Abt, 33. PR, 9. PD

My home town

Part One

Life in a small village can be quite tranquil; you are generally insulated from the fleeting fashions of the big city. In the old days - before the internet, Whatsapp and OnlyFans - it was worse. Important things would happen without the villagers noticing. The death of Charlemagne? They only found out about it weeks later. The Black Death might have been a little more relevant, but the antics of a foreign king and his busty cleaning lady? Not so interesting for a hardworking farmer. Imagine, if you will, the rise and fall of Darth Vader, intergalactic war and all, going completely unnoticed by the inhabitants of a small village on a small planet somewhere in the Outer Rim. They could go from the Old Republic to the New Republic without ever knowing there was a war going on.

In our case, it's World War II. When the Germans invaded, prepared plans were put into action. The population was warned over the radio that war had broken out. Claude, my neighbour at the time, lived through it all. He said that he just noticed that "'Den Duits' was back, again", and then he went back to feeding his chickens. This had happened before:  the Germans, the Dutch, the French, the Austrians, the Spanish, the Romans, they all graced our lands. So he wasn't worried. He had his vegetable garden, his pigs and his chickens; he wouldn't starve. And he didn't.

the Germans, the Dutch, the French, the Austrians, the Spanish, the Romans, they all graced our lands. So he wasn't worried. He had his vegetable garden, his pigs and his chickens; he wouldn't starve. And he didn't.

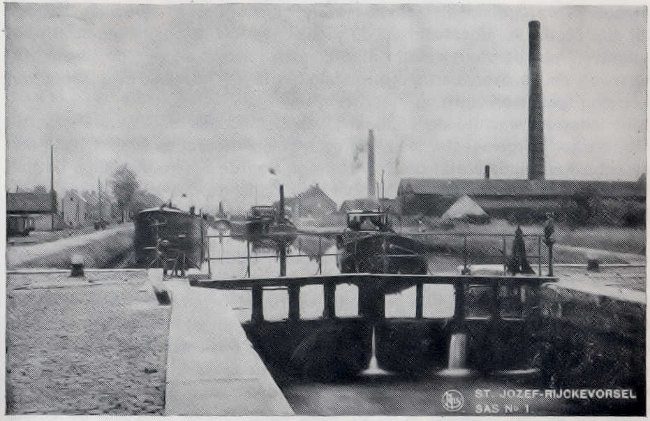

Meanwhile, the French and British thought the best way to keep the Germans at bay was to do what they had done in the First World War, only this time preferably in someone else's country. So they moved north to pin the Germans down along the KW line and up to the Dutch town of Breda, in another Miracle on the Marne. Because Breda was going to be fought over, the entire population had to be evacuated. One of the escape routes was from Breda via Hoogstraten to Antwerp, where they believed they would be safe. The village of Sint Lenaarts (ie. where I grew up) is along this route. They saw the crashing aeroplane (a He-111 from KG4) and apparently some arse tried to bomb bridge no. 9, which I used to cross on my bicycle every single day, on my way to school. They didn't know what else was coming, though.

The Dutch refugees, on their way south to Hoogstraten and Brecht, hindered the Allied troops on their way north. To make matters worse, enemy aircraft were soon strafing both the refugees and the French alike, with machine guns and bombs. The constant hiding in ditches and trenches, the dead and wounded, the exhaustion, the breaking down of bicycles, prams and wheelbarrows all slowed the French advance. During the night the advancing French met the forward screen of the German 9. Panzer Division and the 208. Infantry Division near Minderhout. That village actually saw quite heavy fighting, with StuKa bombing runs, minefields and artillery barrages. Most of the refugees decided here that they'd had enough and went back home, since their city wasn't being fought over, after all.

It's now the 15th of May, and down south, the Germans have just broken through the French defences at Sedan. They were moving a massive force into the French heartland. The French command (Messieurs Giraud and Georges) already believed that all was lost and quickly began to move their forces back to France, including their 7th Army in Breda. The people of Sint Lenaarts did not know this either. But the Germans did. Their 9. PD had been split at Moerdijk (one part going north to Rotterdam and the other south, which is the one this article covers), but it was felt that with the French gone, they could be better used in the north to drive the Dutch into submission. This left infantry regiments 309 and 337 of the 208. ID to advance on Antwerp, through my village. The collective memory recorded some French soldiers marching north, and then retreating through the Houtstraat with the German 337. IR on their heels. Unfortunately, no pictures or notes were made.

After the French troops in Zeeland had been defeated without putting up much of a fight, the Belgians were left alone to defend their country. Four of their infantry divisions successfully defended the northern part of Antwerp, delaying the German forces until the city fell on 18 May after considerable Belgian resistance. Ten days later the whole country folded. This left a bitter aftertaste, but most Belgians thought the war was now over. After all, the Netherlands and France had surrendered as well, and England would probably make a deal with Hitler, or so they thought.

The occupying Germans seemed friendly, the war was over and people were settling into the new reality. Foreign soldiers were not new to the Belgians, the people knew what to do. Which is why Heinrich and Manfred brought some tea or coffee, and were now sitting at the farmer's table, drinking the farmer's beer, admiring the farmer's daughter, and making an effort not to notice the Jewish refugees under the floorboards. Live and let live. That's the Flemish village way.

Biblio

- W. Schoofs, De slag om Brecht, 2005

- C. De Decker en J. L. Roba, Luchtslag boven het kanaal, 1993, Uitgeverij De Krijger

- Lexicon der Wehrmacht. 208. Infanteriedivision

- Wikipeda: invasion of Belgium

- HyperWar: invasion of Belgium

- Brechts Oorlogsmuseum (Dutch)

- TracesOfWar: evacuation of Brteda (Dutch)