Panthers in the mist

"Be careful with your new toys!"

PzKpfw II Ausf. C

- Cherkasskoe, oblast Belgorod, Russia, USSR

- July 6th, 1943

- • “801”, 4. Ko, PzAbt 52, PzGrenDiv „Großdeutschland“

- Oberleutnant Erdmann Gabriel

I think it’s universally agreed that the PzKpfw V “Panther” was technically the best tank of the second world war, in precisely the way that a Lamborghini Huracán is a better car than a Suzuki Swift.

When the Wehrmacht first met the Soviet T-34 they had trouble beating it, so they ordered something better. The result was MAN’s Panzer 5 design, sporting a very good gun, but also every possible technical innovation or funky new system. Then, Hitler decided that he wanted the tanks for his new dream offensive, so the Panzer were rushed into service without proper testing or training. This is why its combat debut became a total, complete disaster.

First off, the tanks weren’t ready in time for the planned offensive, so it was postponed – twice. Because the tanks were still being built, the crews could not train on them. The cooling systems did not work properly, resulting in electrical fires. The driveshafts broke, exhausts exploded from leftover fuel gas, and some sabotage was discovered.

2 fast 4 you

The first 200 Panthers were given to Panzerregiment 39 “von Lauchert” (combining PzAbt 51 and 52), and deployed with Panzergrenadier-division Großdeutschland in the southern area, near Tomarovka and Cherkasskoe. This is a problem in of itself: usually, a two hundred strong tank force is organized as an armoured division, with mechanized infantry, artillery and repair facilities. But no, they were in a hurry, so they made up a regiment (39th) and attached that to an imaginary brigade (10th), minus its required staff officers and equipment.

When their glorious new wonder machines arrived at the starting line, it was one day before the great attack would start. “Just in time, then!”, you might say, but being late meant that the crews would have to attack strong, prepared Soviet positions in untested vehicles, without time to check out the terrain or speak to nearby units. They were, effectively, blind and crippled before the fight. Oh, and on top of that, 52th commander (Major Sievers) fell sick and had to be replaced by Major Teepe, a completely inexperienced teacher from Putlos armoured school.

Now everything was ready; the fight could start. Even if most didn’t realize it then, this would be the last chance for Germany. Losing this battle meant that no hope of victory remained, that all was (nearly) lost. Let’s have a look at Operation Zitadelle, then, and see how our Panthers are doing.

It was smooth on paper, but we forgot the ravine

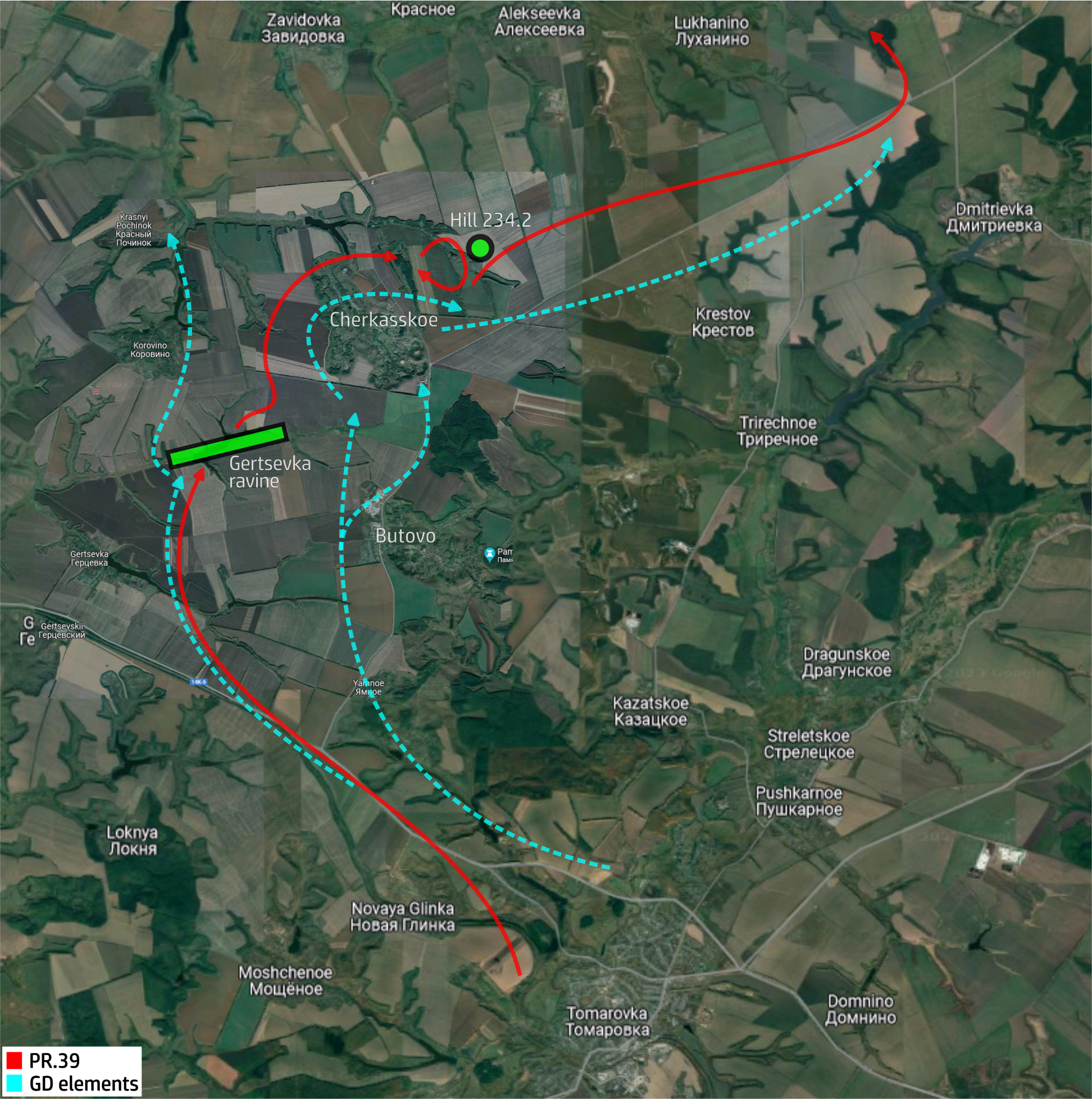

On the 5th of July, Großdeutschland had a couple of Pz IV’s, three Tigers (why?) and one hundred and eighty four Panther tanks at the Tomarovka staging area. Around half past eight in the morning, they went on the attack towards Cherkasskoe, their target for that day. Usually, one would move straight to the north, via Butovo. However, along the way, near Vysokoe, there was a heavily defended hill causing GD to opt for a different path: through Gertsevka, a little to the west…

…which entirely had its own difficulties. You see, to the north of , there’s a small ravine, or rather a small lake. This was now an ant-tank ditch, covered with mines and barbed wire. GD nope’d out and went back to the Butovo route, unfortunately without informing their Panther units. Those immediately bogged down on the muddy lake shore, with their weak transmissions and leaking fuel pumps causing many fires. To make things worse, the Soviet artillery opened and they were attacked by Soviet M3 tanks that were, to be honest, not much of a danger to them. The whole show cost them eighteen of their tanks, and they weren’t even able to capture their assigned target: Hill 232.4, about two kilometers northeast of Cherkasskoe.

Teepe's trial by fire

The next day, things did not go better. For starters, the next day started around four in the morning which is way too early for civilized conversation. Panzerregiment 39 was parked at Yarki, in between Hill 232.4 and Cherkasskoe, preparing to attack towards Lukhanino, when the Soviets started shelling them – again. Major Teepe had had enough at that point: he broke down crying, unable to command, too scared to take action. The whole regiment remained in place, being shot at, until one of the more experienced company commanders, a Oberleutnant Erdmann Gabriel, took up the initiative and got things rolling again. Let’s see what he has to say for himself.

"Using his heavy artillery, the enemy fired such a massive amount of fire into our assembled forces that my company immediately lost two tanks.”, he writes in a letter to Walter Rahn, a colleague. “One slid into a deep trench and the other one was completely destroyed by a direct hit, killing the 4th platoon's leader Master Sergeant Grund and his entire crew. This was a dangerous situation and because we got no orders from battalion command, I ran over to the commander's tank as fast as I could.”

Modern armies teach their soldiers that, when necessary, they should assume command and get the battle going. This is not a given; Soviet soldiers never learned to take initiative. In this case, Gabriel had the right idea: the battalion had to get out of there. His commander wasn’t having any of it, though.

“As I looked into the turret from above, I saw the commander, shaking in distress and incapable of taking action. It was Major Teepe from the Armor Training School in Putlos, whom I knew from my time there. He replaced Major Sievers, the actually battalion commander, who had fallen ill. It was obvious that this kind of baptism of fire, during his first day of action at the front, was too much for him. After I had made it clear that we had to move forward immediately, he could only reply "Yes, Gabriel, get the battalion out of here!".

And he did. He ran back to his own Panther and gave orders to the rest of the batallion: "Follow my tank in direction of attack, move forward immediately!" and in the distance, Russian infantry already started to retreat. “I then made a fire halt, to let the other tanks catch up with me. After my second shot, I was hit by an anti-tank round which penetrated the munitions chamber at the left side, causing it to explode.” If the propellant in tank shells starts burning, that’s called a cook-off. You can tell when it happens, because it involves a massive flame coming from the tank’s inside.

“Following the burst of flames, I was likely unconscious for a moment. Only glowing shreds of my uniform remained on my chest. I tore off my smoldering headset and microphone with my severely burnt hands, which already had the fingernails popped off.”

Well, nice detail. But other people were still in the tank, trying to get out.

“Then the gunner was pushing on from below, but I had to push back his head, because I had to get out of the turret myself. This all happened very fast. I extinguished the glowing remains by rolling in the weeds on the field. I even managed to get the wedding ring off my finger before my hands started to swell. After me, the gunner was still able to rescue himself. He had suffered burns mainly in his face. He already appeared to be losing his mind at the main clearing station that afternoon and was dead by the next morning.”

His driver and radio man were lucky, they had some burns but could still walk back to the safe rear area. Gabriel himself was flown to safety on a Tante Ju and survived the war. Not the loader, though, who was also a journalist. “He appeared to have been killed immediately by the impact of the shell, and remained inside the burning tank”.

The Marne, all over again

By now, a lot of Germans were unhappy. By the end of the day another 37 Panthers were lost and the big push was clearly not going as planned. By the end of August, the battle would be over. The Germans spent their best units and tanks, everything they could have mustered, and for the first time in the war, did not even reach their operational targets. There would be no recouperating from this, too much had been lost.

Or as Guderian wrote: “With the failure of Zitadelle we have suffered a decisive defeat. The armoured formations, reformed and re-equipped with so much effort, had lost heavily in both men and equipment and would now be unemployable for a long time to come. It was problematical whether they could be rehabilitated in time to defend the Eastern Front. Needless to say, the Soviets exploited their victory to the full. There were to be no more periods of quiet on the Eastern Front. From now on, the enemy was in undisputed possession of the initiative.” Meaning, the war was now definitely lost. But it would take a lot of lives for everyone to accept that fact.

Biblio

- http://www.dupuyinstitute.org/ubb/Forum4/HTML/000003.html

- https://mikesresearch.com/2019/10/27/panthers-at-kursk-1943/>

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Kursk

- https://forum.axishistory.com/viewtopic.php?t=109900

- "Panther in Action 1943-45", Solarz